Trauma-Informed Design

*Content Forecast: This blog includes discussion about trauma. These discussions are located in the First, a quick explanation of trauma. section and are broad definitions of trauma, not specific stories.

In recent years, the conversation around mental health has expanded to encompass various aspects of our lives, including the spaces we inhabit. Architecture, traditionally seen as a field focused on aesthetics and functionality, is now exploring a more empathetic approach known as trauma-informed design. This design philosophy prioritizes the well-being of individuals who have experienced trauma, recognizing the profound impact that the built environment can have on their healing journey.

In May of 2023, I attended Trauma Informed Design: Breaking the Stigma, a Webinar by Lynsey Hankins and Sarah Gomez. As someone who has experienced trauma, the emerging field of trauma-informed design is of particular interest to me. It’s also relevant on a large scale to make spaces more comfortable and empowering. One example in the global context is the collective trauma experienced from the COVID-19 Pandemic, which still impacts many of us on different scales.

*First, a quick explanation of trauma.

Mind describes trauma: “Trauma is when we experience very stressful, frightening or distressing events that are difficult to cope with or out of our control. It could be one incident, or an ongoing event that happens over a long period of time.” They explain that “most of us will experience an event in our lives that could be considered traumatic” even though it will affect people in different ways. The effects can last long after the initial incident.

Trauma is sometimes split into three broad categories: acute, chronic, and complex. There are also many types including physical, emotional, collective, cultural, generational, natural disaster-related, and many more.

The Built Environment and Trauma

Our surroundings play a significant role in shaping our experiences and emotions. Trauma-informed architecture acknowledges that traditional design principles may inadvertently trigger or exacerbate trauma symptoms. For example, harsh lighting, loud noises, and confined spaces can be particularly distressing for individuals who have experienced trauma. Conversely, a well-designed and thoughtful space can create a sense of comfort and contribute positively to a person’s healing process.

As Lynsey and Sarah explained, “The goal of trauma-informed design is to use empathy to create environments that promote a sense of calm, safety, dignity, empowerment, and well-being for all occupants.” The lens of trauma-informed design is a broad and intersectional lens. “Design decisions should be filtered through the overlapping lenses of psychology, neuroscience, physiology, and cultural factors”.

Design Considerations

Trauma-Informed Design is frequently talked about in regards to public spaces such as hospitals and educational buildings, but it can be applied to any space that we inhabit. There are many many ways to apply this design, but here are just a few things to consider:

1. Safety and Security:

-

-

-

- Prioritize creating spaces that feel safe and secure.

- Clear wayfinding signs, well-lit areas, and open spaces to reduce feelings of confinement.

-

-

2. Sensory Considerations:

-

-

-

- Incorporate natural light, soft textures, and calming colors.

- Minimize loud noises and disruptive elements

- Include natural elements to your design. There is wide-spread documentation that connection to nature provides physical and psychological health benefits.

-

-

3. Empowerment and Choice:

-

-

-

- Allow individuals to have control over their surroundings when possible.

- Provide flexible spaces that accommodate different needs and preferences.

- People can use their own artwork in communal spaces. Including people in a space gives choice, control, and belonging.

-

-

4. Cultural Sensitivity:

-

-

-

- Recognize and respect cultural backgrounds when designing spaces.

- Reflect inclusivity and avoid triggering cultural trauma.

-

-

5. Community and Connection:

-

-

-

- Foster a sense of community that encourages social interaction.

- Incorporate communal areas and support networks to promote healing through connection.

-

-

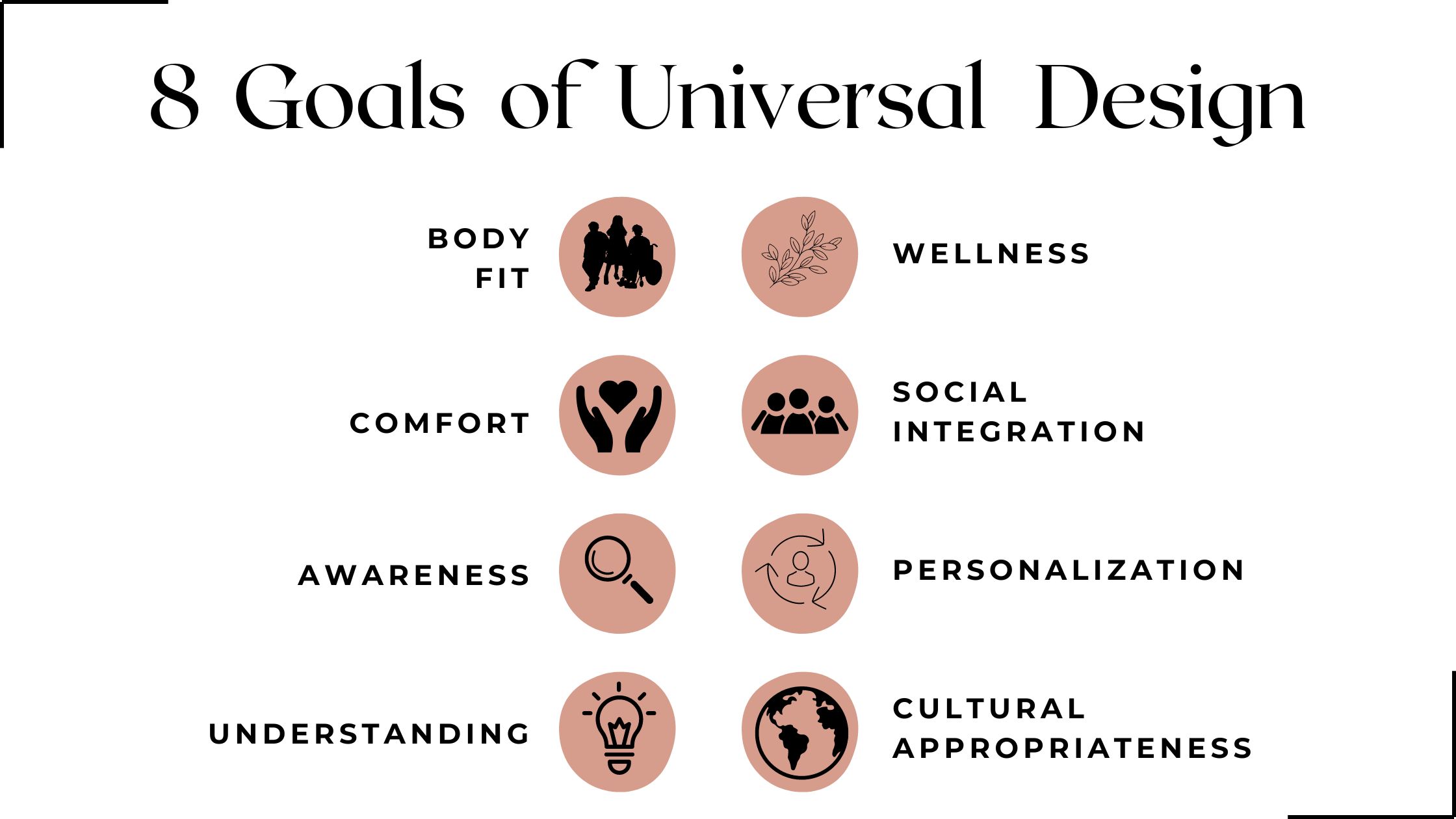

The ways this theory can be applied will differ between buildings and inhabitants, but a few key things to consider are spatial layout, lighting, paint colors, noise reduction, biophilia, adding soothing art and visual interest, and designing with the 5 senses in mind.

Trauma Informed Architecture

Trauma-informed architecture represents a shift in a way we approach design, emphasizing empathy and understanding. As the architecture world continues to explore the intersection of mental health and the built environment, trauma-informed architecture illustrates the transformative power of thoughtful design in fostering healing and resilience. As Architects and Designers, we have the unique opportunity and responsibility to influence people’s lives through the built-environment, and trauma-informed design is an important lens for developing our designs.

Blog written by Asha Beck